ENGLISHMEN LIKE to point out that the Ford GT started life as a Lola. It was a direct development of the 1963 Lola GT, a mid-engined, Ford-powered prototype designed by Eric

Broadley for Le Mans. The Lola dropped out of the 1963 race but obviously had a lot of potential. Ford, eager to get into international racing quickly, established Ford Advanced

Vehicles under Englishman Roy Lunn and retained Broadley and a third Briton, ex-Aston Martin team manager John Wyer, to develop the design as the Ford GT. The new American challenger to Ferrari appeared in April 1964. Thirty-eight months later it ended an up-and-down but eventually fruitful career as the totally changed Mk.4, with almost twice the displacement and a "team" reliability based on multi entries.

There were three basic Ford GTs: the original 4.2/4.7-liter GT-40, which accomplished little as a prototype but later dominated the Sports category with impressive regularity; the 7-liter Mk.2, built on the same chassis, which won Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans and the 1966 Manufacturers Championship; and the much lighter Mk.4, nee J-Car, which won Sebring and Le Mans last year after a seemingly endless gestation period but was unable to prevent Ferrari from recapturing the constructor's title. (The Mk.3 was a road-equipped GT -40 built in England for such wealthy sportsmen as would test Mrs. Castle's 70-mph limit to the full-sort of an Anglo American LM.)

We won't give technical analyses of all the models here it will take all the available space to cover the Ford's four-year, 69-race competition career and describe briefly the several variations of the three basic models that have appeared.

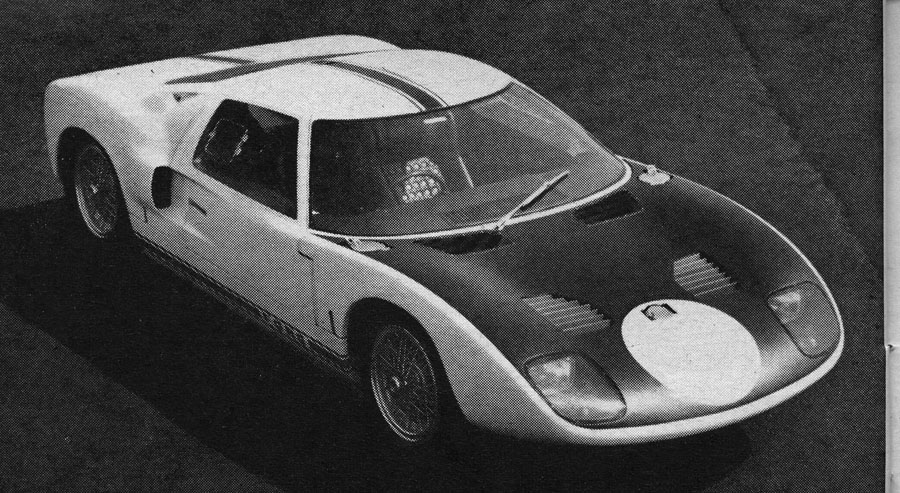

The first Ford GT was shown to the .public in New York. After being completed by FAV at Slough, England, it was rushed across the Atlantic so that its debut could be all-American. English motoring journalists were quick to describe the new car as no more than a glorified Lola; the basic configuration and placement of the 255-cu in. (4.2-liter) pushrod Indianapolis-type engine were very similar to Broadley's original 289-powered car and the center section's wrap-over doors the design's most distinguishing feature-were identical. Informed American writers conceded the inspiration to Broadley and the overall engineering responsibility to Lunn, but kept in mind the fact that the engine and financing came from this side of the ocean. The car's later successful development was totally. American and justified the original billing. Just the same, Ford of Dearborn sent out some ridiculous press material showing, through. spurious styling sketches, how the GT was really developed from the V-4 Mustang I project and strongly related to the then new 1965 Mustang production car Well, the Mustang did have imitation side scoops.

Aside from the multitude of chassis problems that all competition cars must eliminate) through continual race testing, the Ford GT had serious aerodynamic faults which could be ascribed to the styling studio's desire to make it look pretty. It was a handsome, purposeful car, but in its very first outing, the Spring 1964 Le Mans trials, the clean nose underwent the first of a series of surgical operations that lasted two years before an efficient combination of penetration and radiator ducting was worked out.

Le Mans was always the chief target of the Ford campaign, but the team was smart. enough to know that a new design must be run often under varying conditions to become raceworthy. So one GT-40 appeared in the Niirburgring 1000-km race as a warm-up for the French 24-hr event. Three-time Le Mans winner Phil Hill was paired with Bruce McLaren, who had done much of the GT-40's initial test driving; the Ford retired, but not before it had shown itself already competitive to the well-established Ferrari 275P. A three-car entry went to Le Mans, with Richie Ginther/Masten Gregory and. Dick Attwood/Jo Schlesser joining the team. The three cars were identical, with 4.2-liter Indy engines and Colotti transaxles, and shared a consistent white-and-blue color scheme. Ginther / Gregory led the race in the beginning and Phil Hill set a new lap record as dawn was breaking, but all three cars retired.

The basic problem was the Colotti gearbox, though the 4.2 engine was also proving unsuitable. Two weeks later the same entry achieved the same results in the Reims 12-hr race; the, only difference was that the Attwood/Schlesser car had a different engine: the Shelby-developed 4.7-liter unit. Except for one car which ran unsuccessfully in the Nassau Tourist Trophy in November, the 1964 season was over for Ford.

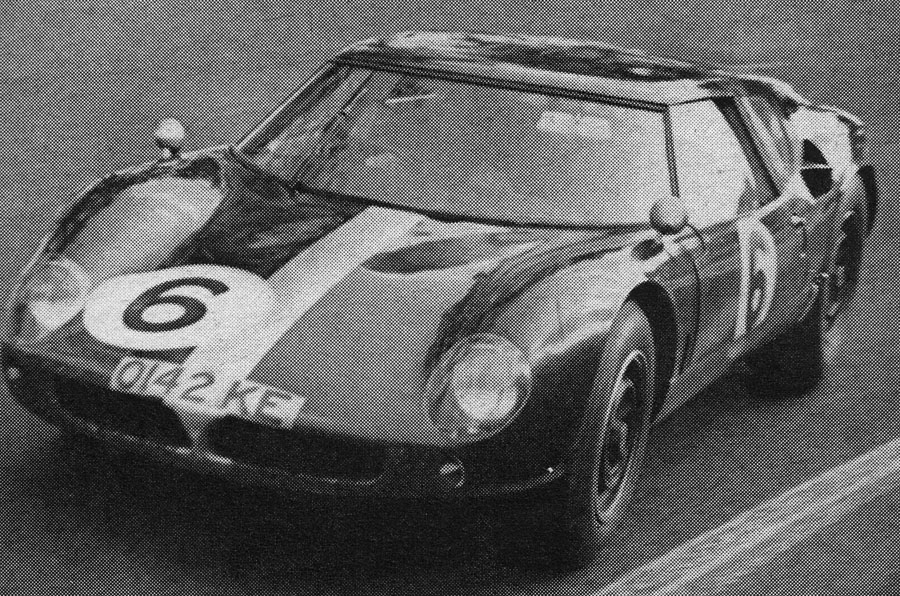

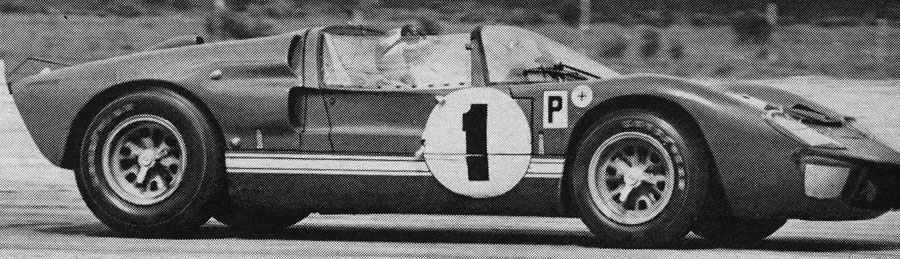

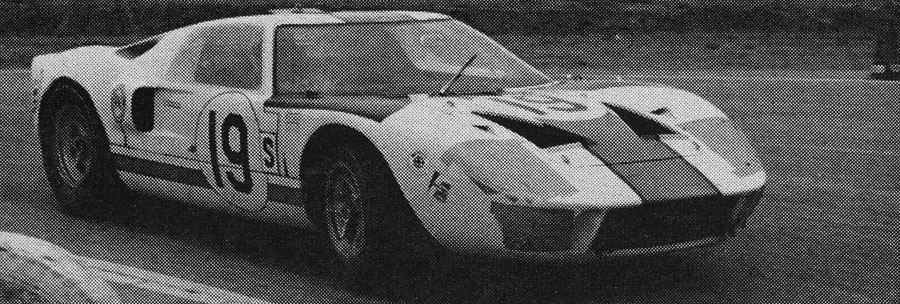

Carroll Shelby's Cobras had come within a whisker of taking the 1964 GT Manufacturers Championship in their first attempt, so it seemed wise to Ford executives to give Shelby American the primary responsibility for developing and racing the GT-40, while letting FAV continue with several cars and adding Ford France, Rob Walker of England and Scuderia Filipinetti of Switzerland to the program. Shelby started modifying his cars in California; the 4.7-liter engine, heavier but with greater torque, became standard for the GT-40 and the gearbox and brakes underwent thorough redesign. Results seemed to be immediate. The Shelby-blue GT-40s finished first (Ken Miles/Lloyd Ruby) and third in the Daytona 200km race and only a Chaparral sports/racirig car beat the McLaren/Miles Ford at Sebring.F A V ran one car in the Targa Florio, a green GT40 roadster entrusted to Bob Bondurant/John Whitmore. The Sicilian circuit has never been kind to large, powerful cars and the Ford retired after various adventures. At the Ntirburgring the car was joined by two Shelby machines (one a 5.3) and another GT-40 for Ford France. The only one to finish was the Chris Amon/Ronnie Bucknum car in 8th place.

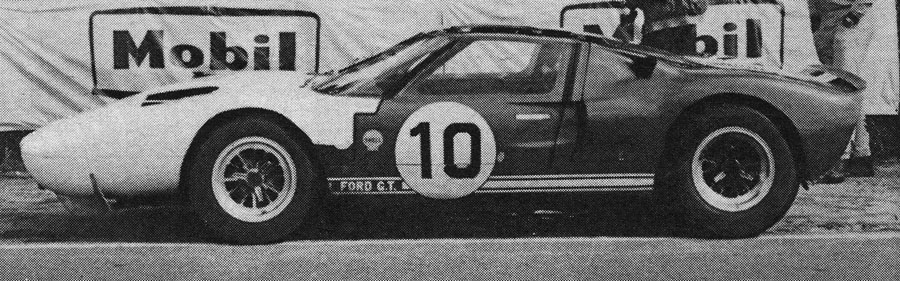

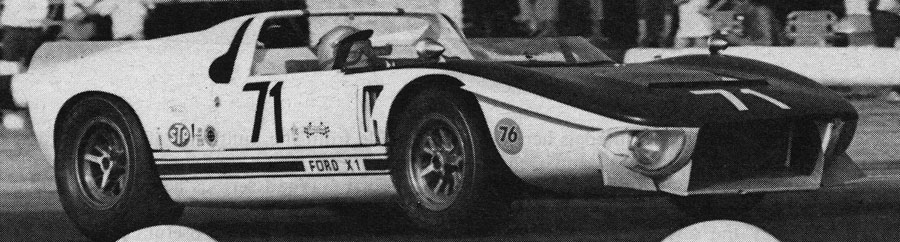

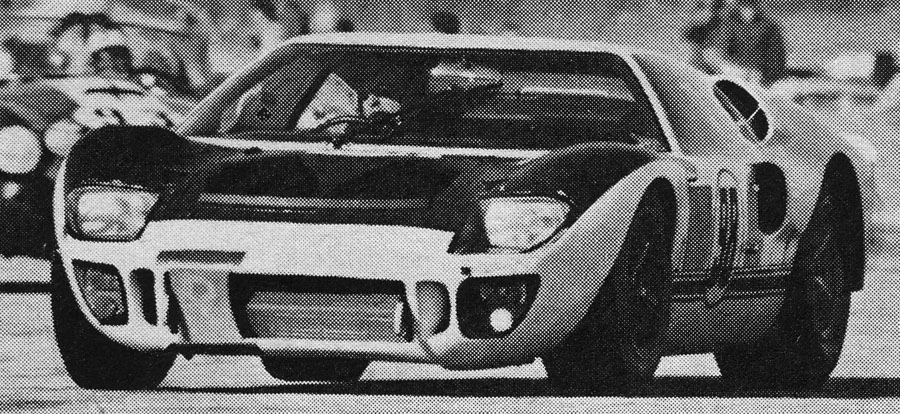

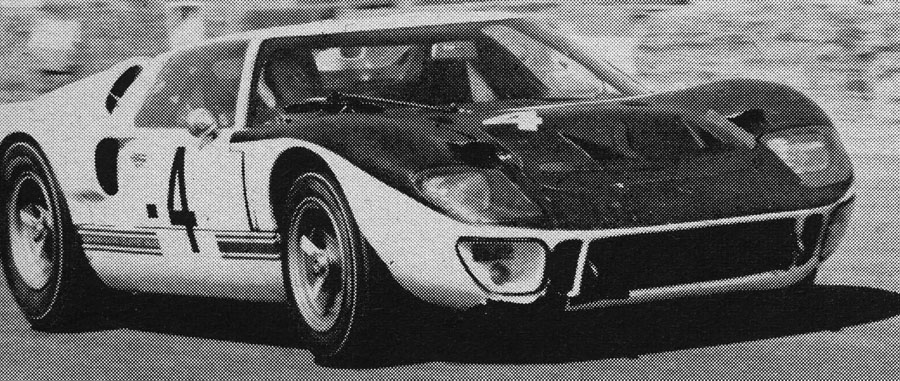

So, again, Le Mans. Someone had decided that 7-liter engines would propel the GT-40s just that much faster down the Mulsanne straight, so the two Shelby-entered cars for McLaren/Miles and Hill/Amon were so equipped. These have been referred to since as Mk.2s, but the designation was not actually applied until the car was redesigned for 1966. The 1965 Le Mans cars had enormously long noses and vertical tailfins and went like blazes. They were backed up by four GT-40s for Walker, FA V, Ford France and Filipinetti. The story of the ensuing debacle has been well told: not a single Ford was running at four o'clock on Sunday. Another year had gone by and Ford didn't seem any closer to the intended Le Mans victory. But the decision was made to stick with seven liters for the prototypes and to build 50 of the GT-40s for the 1966 Sports category. To get some more miles on the 7-liter chassis, Ford gave a long-nosed roadster to Bruce McLaren to run in the Fall 1965 North American pro series. Bruce raced his own McLaren-Oldsmobile but put Chris Amon. in the Ford, known rather sneakily as the GT Xl. An automatic transmission was tried, but automatic or manual, the Xl was too heavy to be competitive with the sports/racing types. Amon drove it at Mosport, Riverside and Nassau, his best placing being a 5th in the Times GP. Peter Sutcliffe gained a second victory for Ford at the end of 1965 when he took the Pietermaritzburg 3-hr race in South Africa in his private GT-40.For 1966 Ford was well prepared. The Mk.2 had been thoroughly tested. and was supplied to Holman-Moody as well as Shelby, while the Essex Wire team received GT-40s to contest the Sports category. The Mk.2s had many detail refinements and were. distinguished. by new medium-length noses and engine air intakes mounted high on the rear quarter panels. They were 1-2-3-5 at Daytona (now a 24-hr race) and 1-2 at Sebring, with Miles/Ruby winning both events. The Sebring-winning Ford was called the Xl but was actually a Mk.2 with the top cut off; though a roadster, it differed in almost every other detail from the car campaigned--by Amon in 1965. At Sebring, Ford began a new practice of painting the team cars different colors (the Sebring winner was a nice Italian red). This probably aided in identifying the cars from the pits but to the casual spectator it also gave the erroneous impression that a half dozen private teams were using Fords to battle one another. Ferrari offered no resistance at Daytona and sent only a token P3 to Sebring.

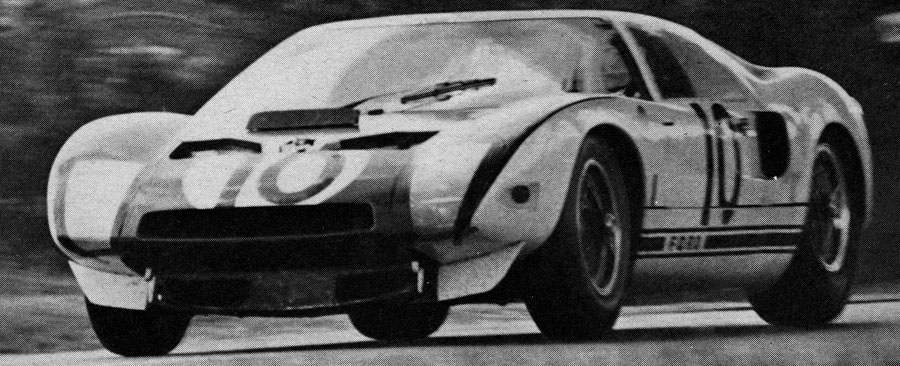

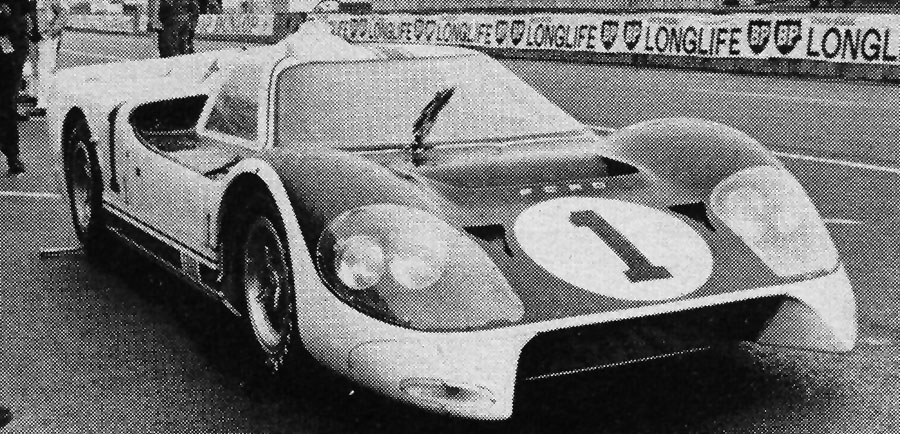

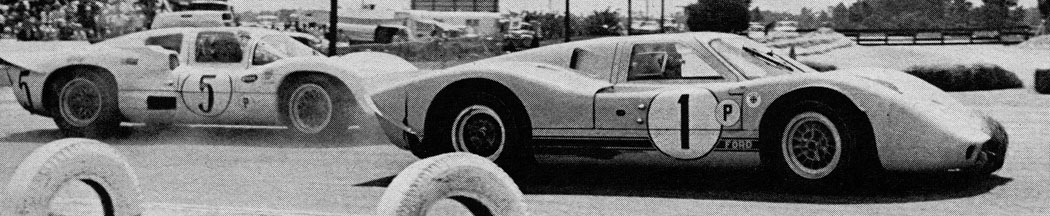

Meanwhile Ford had been hard at work on the J-Car-a new lighter car that proved to be as ugly as the original GT40 had been tidy. The J-Car ran in the Le Mans trials in April but was slower than the Mk.2 and much slower than the Ferraris. Its body featured a low, pointed nose, an angular midsection and a severly chopped tail. It didn't handle well and its racing debut was postponed to 1967- probably the wisest decision Ford made. Only the GT40s showed up for the Monza 1000-km race, won by a lone Ferrari P3. Whitmore/Gregory (the latter back on Ford's side after winning Le Mans for Ferrari in 1965) came 2nd overall to win the Sports category. At Spa a Mk.2 made Its European debut, entered by Alan Mann Racing for Whitmore/Frank Gardner. It was outclassed on the sweeping Belgian cirsuit by the Mike Parkes/Lodovico Scarfiotti P3 but took 2nd place ahead of three GT-40s, which by LOW weren't getting much opposition from the Ferrari LMs. And again Le Mans. There was a lot of bad-mouthing when Ford entered no less than eight Mk2s, backed up by five GT-40s, but Ford had learned about Le Mans attrition and wanted insurance. As it turned out, only three of the 13 Fords went 24,hours, but they were 1st, 2nd and 3rd. A cute finishing strategy prevented the race-long leaders, Ken Miles/Denis Hulme; from taking a deserved victory; this seemed especially sad later in the year when Miles lost his life testing the J-Car at Riverside. No one; had done more to make Fords race winners than Miles. Ford won the 1966 Manufacturers Championship with the three wins at Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans and the 2nd at Spa.In addition to the GT-40s raced by the major Ford exponents in the international Sports category, a number were campaigned by true private owners, primarily in England. Three minor wins were scored in GT-40s at Crystal Palace (Peter Sutcliffe), Croft (Eric Liddell) and a repeat in the Pietermaritzburg 3-hr (Mike Hailwood/David Hobbs).

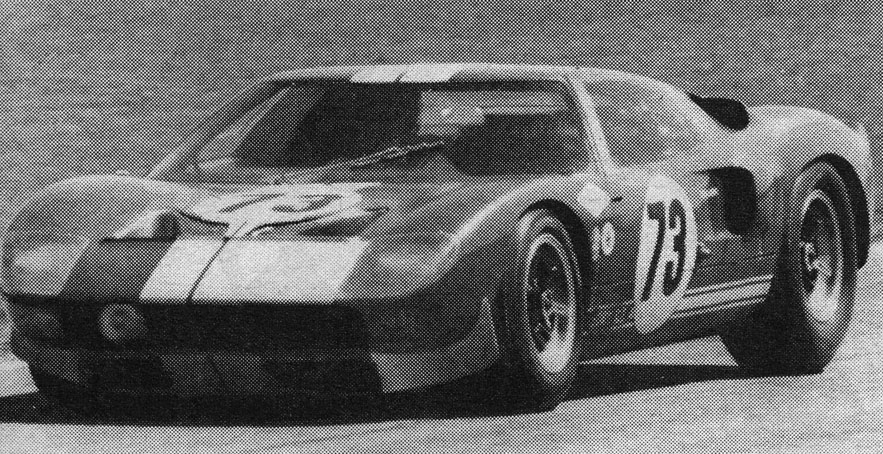

The 1967 season is recent enough not to require much (;om.. ment. Transmission failures knocked one Mk.2 after another out of the Daytona 24-hr race, the best-placed Ford being the Jacky Ickx/Dick Thompson GT-40, entered by John Wyer under his new firm, J.W. .Automotive Engineering. Sebring saw a triumphant debut for the J-Car, now better streamlined and finally respectable enough to join the official line-up as the Mk.4.Wyer was out to show Ford what could have been done to the original GT-40 design; the resulting Mirage prototype won convincingly at Spa from the Chaparral and the Ferraris. The Mirage was a much-lightened, better streamlined car which used 5.1 and 5.7-liter Holman-Moody prepared versions of the 4.7-liter 'Cobra engine. Sponsored by Gulf Oil and painted a striking light blue with orange trim, the Mirage benefitted from the virtuoso driving of Belgian comingman Jacky Ickx. Later in the season Mirages won the Paris 1000-kl)1 race at Montlhery and two minor events at Skarpnack, Sweden and Kyalami, South Africa.

Once more, Le Mans. Twelve Fords (four Mk.4s, three Mk.2s, three GT-40s and two Mirages) were deemed sufficient, but ten would have been too few - only two finished. The surprise was that the two winning drivers were Dan Gurney / A.J. Foyt, a pair not thought to be of long-distance race temperament.

As far as Dearborn was concerned, the GT campaign ended last June with the second Le Mans victory. Ford announced its withdrawal from prototype racing to concentrate on stock cars and Group 7 machinery, a decision prompted by the 3 liter limit on prototypes for 1968 but probably one that had already been considered. Ford France continued to race a Mk.2 after Le Mans, winning the Reims 12-hr race, while Paul Hawkins, won five minor races in his private GT-40.

The GT-40 will probably be a strong competitor for overall victories in 1968 races (5-liter Sports Cars are allowed). Ford's entry into Group 7 racing has been conspicuously unsuccessful, but it took three years to win Indianapolis and three years to win at Le Mans, so 1969 may be Ford's big year in the Canadian-American Challenge Cup.

Author: ArchitectPage