Written in 1964

IN THE YEARS between the first and second World Wars, Aston Martin established a reputation second to none for high-quality sporting cars. They were among the fastest in their class and price was always a secondary consideration.

Since 1947 Aston Martin has been a member of the David Brown Group and has built Grand Touring and sports racing cars, which rank among the world's fastest.

Aston Martin emanated from the motor repair business run in South Kensington by Lionel Martin and Robert Bamford. They were agents for Singer cars and Martin successfully converted a sedate 40 m.p.h. Singer tourer into an 50 m.p.h sports car. Many customers wanted their cars similarly modified, but Martin did not think that this was practicable and decided instead to build a sports car from scratch. He used a 1,390 c.c. (66.5 X 100 mm.) 4-cylinder Coventry Simplex engine and installed this in an elderly 1908 Isotta Fraschini voiturette chassis. The car was called Aston Martin, the Aston part referring to Aston Clinton Hill near Aylesbury, where Martin had driven his Singer.

The outbreak of war stopped development, but another car was built in 1919, using the same engine in an 8 ft. 6 in. wheelbase chassis designed by Martin, with quarter elliptic springs at the front and semi-ellipfics at the rear. Transmission was via a 3-speed constant-mesh gearbox and cone clutch to a fully floating bevel gear rear axle. Further prototypes appeared in 1921, with a largely redesigned engine, a multi-plate clutch, a 4-speed gearbox and an 8 ft. 7.5 in. wheelbase.

As it was clear that Aston Martin had little chance in track events so long as the side-valve engine was used, S. Robb was commissioned to design an o.h.v. unit. This was a single overhead camshaft 16-valve design, with unit cylinder head and block of 1486 c.c. (65 X 112 mm.). In May 1921, Count Louis Zborowski with a 16-valve track car broke the standing start class records at Brooklands for the mile and kilometre at speeds of 66.82 m.p.h. and, 60.09 m.p.h. This provided a fitting introduction for the first six side-valve chassis, which were sold that winter at a price of £500 or £650 with 2/3 seater tourer bodywork.

The 16-valve engine did not prove as fast as was hoped, and Clive Gallop, who looked after Zborowski's racing cars and had beeh apprenticed at Peugeot, was sufficiently acquainted with Marcel Gremillon to persuade him to supply drawings of the 3-litre Ballot cylinder head and block. These were scaled down and two new engines were constructed using the Robb-designed block and Ballot cylinder head design.

These units developed 54 b.h.p. at 4,500 r.p.m. Two cars were entered for the 1923 French G.P. at Strasbourg, but retired with magneto trouble. Shortly afterwards Zborowski was 2nd in the Premio Penya Rhin in Spain. Other successes were gained during the year at Brooklands and at Shelsley Walsh, Aston Clinton, Kop and Beacon Hill-climbs. Even if few production cars were yet sold, the make had established an excellent reputation. Wire wheels and 4-wheel brakes were now fitted to the production cars and standard and short-chassis versions were offered. A Super Sports model powered by the 16-valve engine was added to the range, but very few sold. By the time production of the side-valve cars ceased, only around sixty had been made.

To challenge the record breaking supremacy of A.C., Lionel Martin evolved the famous "Razor Blade" in 1923, so called because of its appearance. To reduce frontal area, the chassis and body were built as narrow as possible. The track was mere 3 ft., and the body, at its widest point, measured only 18.5 ins. Mechanical components were as for the Grand Prix cars, except that no differential was fitted. Although Sammy Davis lapped Brooklands at 104 m.p.h., tyre troubles caused the record attempt to be abandoned. Later "Razor Blade" gained many successes in sprint events.

The company was now in severe financial difficulties, and to prevent liquidation, control passed in 1924 to the Chamwood family, but Lionel Martin remained a director. Lady Chamwood's son, the Hon. John Benson, designed a new 4-cylinder twin overhead camshaft engine, but this was a complicated design and was not a success. A car with the Benson engine ran in the 1925 Brooklands 200-mile race without success, and this was the company's sole racing activity in a stagnant year. In late 1925, a receiver was appointed.

The same year the company was reformed as Aston Martin Cars Limited, with new premises at Feltham and a new board of directors, of whom the principal members were Baron Chamwood and W. S. Renwick and A. C. Bertelli, who had previously been working on a I.5-litre car to be marketed under the initials of "R & B". The existing side-valve Aston Martin gave way to an entirely new design, which appeared at the 1927 Olympia Motor Show. The engine was a 4-cylinder 1,488 C.c. (69.25 X 99 mm.) o.h.v. unit with the crankcase and cylinder block cast in one to obtain utmost rigidity and a detachable cylinder head. Transmission was by a 4-speed gearbox with a right-hand change to an underslung worm drive back axle. Rudge Whitworth knock-on hubs and wire wheels were standard. Two chassis types were offered, the "T" type and the "S" sports model. The former had a 9 ft. 6 in. wheelbase and was available as standard with 4-door saloon or open tourer bodywork. The sports model had a shorter wheelbase of 8 ft. 6 in. and was priced at £495 in chassis form or with three-seater bodywork at £575.

In 1928 two Aston Martins were entered for Le Mans and, although both retired, they were notable. for the use of dry sump lubrication; the oil tank held approximately 2.5 gallons and was mounted below the front dumb irons. The Le Mans cars were lighter than the production prototypes and also had the distinction of being the first Aston Martins to bear the familiar winged badge. A year later the "International" model based on the cars raced was added to the range. With a weight of 19 cwt., it had a top speed of 80 m.p.h., some 10 m.p.h. faster than its stable-mates. In 1930 the "International" was fitted with a more imposing radiator and at extra cost the "Ulster" engine developing 56 b.h.p. at 4,500 r.p.m. was available. An open propeller shaft and an E.N.V. bevel gear rear axle were fitted from early 1932.

A. C. Bertelli and C. M. Harvey finished 5th at Le Mans in 1931 and won their class, with a special "Le Mans" version developing 70 b.h.p. at 5,000 r.p.m. With the hope of following up this success, three cars were entered for the 1932 event of which two finished, NewsomefWidengren taking 5th place and winning their class and Bertelli/Driscoll were 7th and won the Rudge Biennial Cup.

At the Motor Show that year, the new production "Le Mans" model was exhibited together with a revised version of the "International". The former was of particularly attractive appearance with a 2/4 seater body of purely functional lines, twin chromium plated flexible pipes, cycle wings and a 19 gallon rear-mounted slab fuel tank. With a power output of 70 b.h.p. at 4,750 r.p.m., the company was able to guarantee a top speed of 84 m.p.h. The "International" on the other hand now had a lower compression ratio of 6 : 1 and developed 55 b.h.p. at 4,500 r.p.m.

Another change in the management of the company came in late 1932, when Sir Arthur Sutherland assumed control and his son, R. Gordon Sutherland, became joint managing director with A. C. Bertelli. The company's policy of making a regular entry at Le Mans was unaffected and in 1933 Driscoll/Penn-Hughes won their class at 65.9 m.p.h., setting in the process a new class record of 73.3 m.p.h., Bertelli/S. C. H. Davis in 2nd place an exceptionally pleasant "car to drive, with delightfully high-geared steering, a heavy, but effective central gearchange and very powerful brakes; it would cruise effortlessly at 70 m.p.h., but the rather heavy weight affected both acceleration and fuel consumption.

The same year the "Ulster" appeared, the most outstanding pre-war Aston. The engine had a special Laystall crankshaft, with larger main 'bearings, 8.5 : I c.r. and twin S.U. carburetters. The model'developed 80 b.h.p. at 5,250 r.p.m. and was guaranteed to attain 100 m.p.h. The body was of particularly handsome lines, about 8 in. narrower than the Mk. II model, there were no doors, but cutaway sides and twin aero screens. The appearance was rounded off by close-fitting aluminium cycle wings, external fishtail exhaust and a facia with a profusion of instruments and switches.

Aston Martin had a field day at Le Man,s in 1935, with an "Ulster" driven by C. E. C. Martin/Charles Brackenbury in third place, having covered 1,865 miles at 75.23 m.p.h., winning the Biennial Cup and other Astons in 8th, loth, IIth, 12th and 15th places.

After a production life of ten years, the I.5-litre engine was replaced in 1936 by a 1,949 c.c. (78 X 102 mm.) 4-cylinder, wet sump, single overhead camshaft engine designed by Gordon Sutherland. This was designated the 15/98 and had synchromesh on three upper ratios and hydraulic brakes. Wheelbase was 9 ft. 8 in. and there was a choice of 4 seater saloon or tourer models or the" Speed Model" 2-seated which at £825 was the dearest of the range. The "Speed Model" had a top speed of around 90 m.p.h., while the standard 15/98 was capable of just over 80 m.p.h. and could accelerate from 0-60 m.p.h. in 20 secs. Henceforth the works took no active part in competitions, but an "Ulster" won its class at Le Mans in 1937 and was 5th overall. Chief Engineer, Claud Hill, unveiled a startling new model at the 1938 Motor Show. This was the "C"-type Speed Model", with an unchanged chassis, but the body was a remarkable attempt at streamlining. This was of "peardrop" shape," with cowled radiator, cycle wings and a long tapering tail.

The outbreak of war in 1939 brought production to a halt, but development of the "Atom" saloon continued. It used the existing 2-litre engine but the body and chassis were combined in one unit welded up from square section steel tubes, to which the panelling was bolted. Front suspension was independent by coil springs and there was a Cotal electric gearbox. By 1946 Claud Hill also had ready a new 1,970 c.c. (82.55 X 92 mm.) engine, with push-rod operated valves, a sound if undistinguished design.

The first post-war Aston Martin victory was in the 1946 Spa 24-hour race, but the winning car was a pre-war 2-litre "Speed Model" driven by St. John Horsfall/Leslie Johnson.

The following year David Brown acquired the goodwill, name and design rights for both Aston Martin and Lagonda, and in 1948 a works entry appeared in the Spa 24-hour; this was an open 2-seater, which won in the hands of Horsfall and Johnson. At that year's Motor Show, not only was a Sp replica exhibited, but also the new DB1, which was made in small numbers until 1950. This had the 1,970 c.c. engine, developing 95 b.h.p. at 5,000 r.p.m. in a welded tubular chassis and a 3-seater body of unusual lines.

Three new cars were built for the 1949 Le Mans race and these were forerunners of the D B2; although they used the existing Aston Martin chassis, they had aerodynamic 2-seater saloon coachwork and one was fitted with the 2.6 litre Lagonda engine. The 2-litre cars finished 7th and 11th, while the larger car retired with radiator trouble. A few weeks later at Spa, St. John Horsfall drove a single-handed race at the wheel of his" Speed Model" and the Lagonda powered car won the 3-litre class.

It had been hoped to race the production cars in 1950, but they were not fast enough and so the DB2 was evolved. At this time the development team consisted of John Wyer, four mechanics and a foreman-some ten years later this had increased sevenfold. It is appropriate at this stage to consider the specification of the DB2, as it formed the basis of all subsequent David Brown designs. The DB2 had the 2,580 C.c. (78 X 90 mm.) Lagonda engine in a frame welded up from square section tubing. Front suspension was by twin trailing links, the lower pair joined by an anti-roll bar and at the rear there was a rigid axle located fore and aft by trailing links and latterly by a Panhard rod. Steering was by worm and roller, there were knock-on wire wheels and 12-in. brake drums. The body was an elegant 2-door h.f.c. of Italian styling constructed in light alloy panels.

The team had a successful season in 1950, for the DB2'S took 5th and 6th places at Le Mans and won the 3-litre class and took first three places in their class in the Tourist Trophy. At the Earls Court Show the DB2 became a production car and was subsequently offered with the Vantage engine developing. 123 b.h.p. at 5,000 r.p.m. (compared with 105 b.h.p. for the standard version) and d.h.c. bodywork. Top speed was around 110 m.p.h., with 90 m.p.h. available in 3rd and a fuel consumption that bettered 20 m.p.g. The model was timed from 0-60 m.p.h. in 10.8 secs. and 0-100 took just under 36 secs.

Doctor Eberon von Eberhorst, of Auto Union fame, joined Aston Martin in 1950 specifically to design a sports/racing car. A stop-gap was needed for 1951 and so lightweight versions of the DB2, using Weber carburetters, were built. The fruits of these modifications were seen in 3rd (Macklin/ Thompson), 5th (Abecassis/Shawer-Taylor) and 7th places (Parnell/Hampshire) at Le Mans, with private owners 10th and 13th. In addition Aston Martins won their class at the Silverstone production sports car race and in the Mille Miglia. The DB2 remained in production until the end of 1953 and was one of the most successful British sporting cars. Meanwhile work has been progressing on the DB3, the new sports/racing car and the prototype appeared in the 1951 Tourist Trophy, but retired with a broken exhaust. The DB3 had a tubular ladder-type frame, with the now familiar trailing link front suspension; there was rack-and-pinion steering and at the rear, a de Dion axle, located by trailing links and a Panhard rod. Rear brakes were mounted inboard. At Silverstone, in May 1952, the three works DB3's were 2nd, 3rd and 4th to Moss's larger Jaguar XKI20C. Motorcycle champion, Geoff Duke, was given a drive a few weeks later in the British Empire Trophy, but retired with ignition trouble. The same week-end a full team appeared at Monte Carlo, but achieved no success. These three cars had an enlarged 2,922 C.c. (83 X 90 mm.) engine and developed 163 b.h.p. at 5,500 r.p.m.

All three works DB3'S retired at Le Mans in 1952, with a variety of minor mechanical failures, but Feltham honour was upheld by the privately entered DB2 of Clark/Keen, which finished 7th. Aston Martin fortunes looked up after this, as Abecassis and Parnell finished 3rd and 4th in the Jersey Road Races and Parnell won his class in the 100-mile race at Boreham. The Goodwood 9-Hours Race was won by Collins/Griffiths with a 2.6-litre car. The last major success for the DB3 was 2nd place in the 1953 Sebring 12 Hours race.

The next stage in development was the introduction of the DB3S, which was lighter and had a smaller frontal area. Wheelbase was reduced to 7 ft. 3 in. and track from 4 ft. 3 in. to 4 ft. I in. Enlarged valves and a modified camshaft boosted power to 192 b.h.p. A full team appeared at Le Mans, but all retired; after that, Astons won every race entered during the 1953 season.

At the 1953 Motor Show, the DB2 was supplanted by the DB2-4, with occasional rear seats, a much larger fuel tank and a bigger boot, to which access was gained through the hinged rear window. The Vantage engine was now standard, but in 1955 this was replaced by the enlarged 3-litre unit, developing 140 b.h.p.

Development of the DB3S continued during the winter and the 1954 model appeared with the rear brakes mounted outboard, to overcome heat dissipation problems. After finishing 3rd in the Buenos Aires 1,000 kilometres race, a full team turned out for the May Silverstone meeting. Two other new David Brown cars raced at this meeting - the 4.5-litre V 12 Lagonda and a f.h.c. version of the DB3S. The latter had been developed in conjunction with Vickers and drag was 25 per cent less than with the open cars, but inexplicably performance showed no improvement and, after two cars were written off at Le Mans, no more were built for racing. Six cars appeared at Le Mans, including the privately owned DB3S of Carrol Shelby. These consisted of a Lagonda, an experimental DB3S, supercharged to discover what stress the unit would stand, the two coupes, fitted with new twin plug cylinder heads and developing 225 b.h.p. at 6,000 r.p.m. and two normal open cars. The Lagonda damaged its rear lights in a minor accident, Stewart and Bira crashed the coupes, Shelby/Frere retired with a broken stub axle. Colas/ de Silva Ramos with transmission trouble and the supercharged car of Parnell/Salvadori blew a gasket. A dismal day for David Brown. Only by a tremendous effort did the team manage to appear at Silverstone a few weeks later, but it was worth it, as the Lagonda (Parnell) finished 4th and Collins, Salvadori and Shelby took first three places. In the Tourist Trophy, run on a handicap basis, two cars retired and the third DB3S finished a very poor 13th.

After the 1954 Motor Show, the DB3S was put into production and by 1957 around a 100 had been built; in production form, the single plug head was retained and power output was 180 b.h.p. at 5,500 r.p.m. (later raised to 210 b.h.p.). For the 1955 season the works cars had a strengthened crankshaft and new connecting rods. The fitting of Girling disc brakes on all four wheels brought a much needed improvement and power output was now 244 b.h.p. at 6,000 r.p.m. At last Aston Martin were able to compete with their principal rival Jaguar on equal terms on all circuits. 1955 proved to be a very good season for the team and successes included 3rd place at Le Mans (Collins/Frere), 1st and 3rd in the Goodwood Nine-Hours race, 4th and 7th in the Tourist Trophy as well as a number of victories in minor events.

At the end of 1955 a special single-seater version of the DB3S was built to compete in the series of races taking place in New Zealand during the winter. It had been intended to use the 3-litre supercharged engine, but eventually a 2.5-litre unit was fitted and in most respects the car was similar to the works sports/racing cars. After arriving too late to compete in the New Zealand G.P., the monoposto Aston took 2nd, 3rd and 4th places in the other races. At this time the Eompany had no definite plans to Grand Prix racing-this was simply another phase in the David Brown development programme.

Changes to the works DB3S cars for 1956 included dry sump lubrication, mainly to reduce frontal area and as the season progressed, the bodywork of each works car was fitted with a more streamlined nose and a streamlined headrest. The team was now led by Stirling Moss and there was every prospect of a very successful season. Getting off to a good start, Salvadori/Shelby won their class and finished 4th overall in the Sebring 12-hours race. Three cars were for the 1956 Le Mans race, including the entirely new DBRl/250 model with a 2,492 C.c. (83 X 76.8 nun.) engine, space frame and a 5-speed gearbox integral with the rear axle. Not surprisingly on its first appearance the DBRl retired (with rear axle failure), but the Moss/Collins DB3S finished 2nd to the Ecurie Ecosse Jaguar and won its class.

By 1957 a team of 3-litre DBRl/300 models was ready to race. The chassis (wheelbase 7 ft. 6 in., track 4 ft. 2 in. was identical to the DBRl/250, but engine capacity was now 2,922 C.C. Both cylinder head and block were cast in aluminium alloy and power output was 250 b.h.p. at 6,300 r.p.m. There was also a 3,670 C.C. (92 X 92 nun.) version known as the DBR2. After a win in the Spa sports car race and a victory in the Nurburg 1,000 kilometres race, three cars were entered for Le Mans, but two retired with gearbox trouble and Tony Brooks crashed, when in second place. Feltham honour was saved by the privately:entered DB3S Colas/Kerguen which won its class.

A new production model appeared in mid-1957, at first only for export. The new DBMk.III had a new radiator grille reminiscent of the DB3S and a power output of 162 b.h.p. or 178 with the optional twin exhaust system. Girling disc brakes were fitted to the front wheels and optional extras included overdrive and even Borg- Warner automatic transmission. The DBMk.III remained in production until the end of 1959.

In the search for increased power, a revised version, the DBR3/3oo had been produced, with a new 2,990 C.c. (92 X 75 mm.) engine, which had twin overhead camshafts operating the valves at 80 degrees and six single-choke Weber carburetters. This also had a new space frame with wishbone i.f.s. using longitudinal torsion bars and torsion bar de Dion rear suspension. Apart from a brief appeanlhce at Silverstone in 1958, nothing more of this was seen until the introduction of the DBR4, as David Brown elected to use the existing cars.

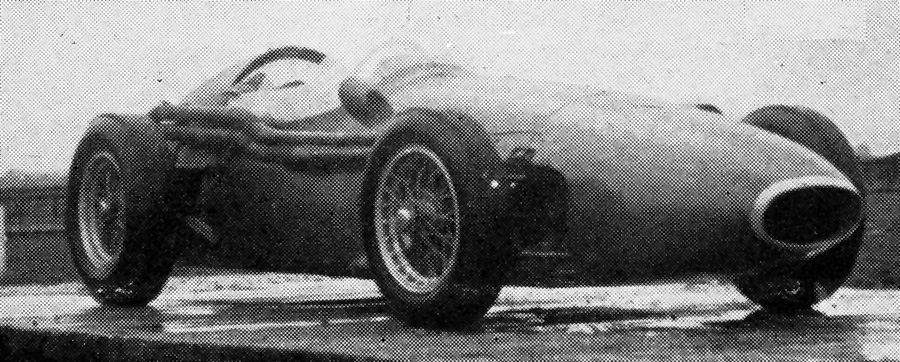

A single DBR1 (Moss/Brooks) was entered for the 1958 Targa Florio, but it retired on the 5th lap, although this car again won at the Nurburgring. All three cars retired at Le Mans but the privately entered DB3S of Peter and Graham Whitehead took 2nd place. Ferrari withdrew his entry in the Tourist Trophy because of transport'difficulties, so Aston Martin took first three places in high-speed demonstration run. Having achieved success in sports/racing events, David Brown now felt ready to have a go at formula I as well, but to compete in both forms of racing threw a tremendous strain on the competition department. The power unit of the G.P. car, the DBR4/250, was based on the experimental DBR3. Engine capacity was 2,440 C.c. (83 X 75 mm.) and 280 b.h.p. was developed at 8,250 r.p.m. Many mechanical features were common to the BDR1, but front suspension was by transverse ball-jointed wishbones and coil springs enclosing Armstrong telescopic dampers. After an initial promising appearance at the 1959 B.R.D.C. Trophy meeting, entries were made in various Grands Epreuves, but for 1959 the design was too bulky and cumbersome and the cars were hopelessly slow in comparison with their rivals. The cars were withdrawn from racing and eventually sold in Australia where they were raced with 3-litre engines.

As the David Brown team was having difficulties in preparing cars for both sports and formula 1events, no entry was made for the 1959 Targa Florio. A solitary car was entered at the Nurburgring and happily Moss/Fairman, giving the make a hat trick in this event. This was followed up a month later by victory at Le Mans after numerous post-war attempts and thirty-one years after the make's first appearance at the circuit. Salvadori/Shelby took first place with Trintignant/Frere 2nd.

With two outright wins, Aston Martin were anxious to win the Tourist Trophy and Goodwood and clinch the Sports Car World Championship. Once again a team of three cars were entered and Moss took the lead at the start with Shelby in 2nd place. During refuelling, a disastrous fire eliminated the Moss/Salvadori car; Moss hastily took over the Shelby/ Fairman car, which had slipped to 3rd place and by driving as only he could, regained the lead and went on to win with the Trintignant/Frere car in 4th place. So the Sports Car World Championship was won and the Aston Martin team, able to rest on its laurels, withdrew from racing.

For some while the name of Aston Martin was absent from the circuits, while the company concentrated on production of the DB4 introduced at the 1958 Earls Court Show, the DB4GT and the current DB5 derived from it. The introduction of the DB4GT and the lightweight Zagato version permitted private owners to compete on reasonably even terms in GT racing. It has however only been since the introduction of the special Le Mans 4-litre GT cars that there have been indications of the make's potential domination of this category. There could have been no better omen for the competition future of Aston Martin than Salvadori's defeat of the works Berlinetta at Monza in September, 1963. Unfortunately Aston Martin have again withdrawn from racing and the works cars have been sold to private owners, but it cannot be too long before a works team again represents the make on the circuits.